Is your Behavioral Crisis Management System Really Trauma Informed?

Trauma associated with events like abuse and neglect can occur at any point in somebody’s life. Not surprisingly, these types of experiences are frequently reported by those receiving behavioral and mental health services, especially by children and adolescents in foster or residential care and individuals with developmental disabilities. Researchers and advocates frequently cite “trauma-informed care” as essentially knowing the history of past and current abuse of an individual and designing service systems that are sensitive to these traumatic experiences and directly involve the individual as a participant in the design and implementation of treatment and education.

Most crisis management systems focus on de-escalation, physical crisis intervention techniques, and are otherwise rooted in mainly coercive approaches.

Since the concept and term “trauma-informed care” received growing recognition, it’s not surprising there are several crisis management systems now touting trauma-informed approaches. Sure, they create amazing graphics, use warm and fuzzy words, and even develop training with titles like Trauma Informed Care approaches. But if you lift the hood and take a deeper look at the strategies used, you find these approaches are in fact, not trauma informed. Most crisis management systems focus on de-escalation, physical crisis intervention techniques, and are otherwise rooted in mainly coercive approaches. They call their de-escalation techniques ‘prevention,’ yet their 'prevention techniques’ do not start until the individual shows the first signs of escalation. If anything is linked to prevention, it might be 1 or 2 concepts, and those are glossed over.

When compared with a system that totally aligns with the Trauma Informed Care concept, such as PCM, the differences are striking. For example, prevention in the PCM system begins before the individual arrives at the facility. Detailed historical records and past evaluations are collected and used and analyzed to create a framework for real prevention through treatment and education. Nothing compares to the more than 100 prevention strategies outlined in detail in the PCM curriculum that consider both the individual’s and the practitioner’s histories.

Individuals and Families Want a Complete System that is Trauma Informed

People who struggle with behavioral and mental health issues desire approaches to crisis management grounded in positive reinforcement. So do their loved ones. They want to be treated with dignity and respect and regularly provided choices and feedback to assist in learning, even during a crisis event. And they certainly want to avoid any type of pain or distress.

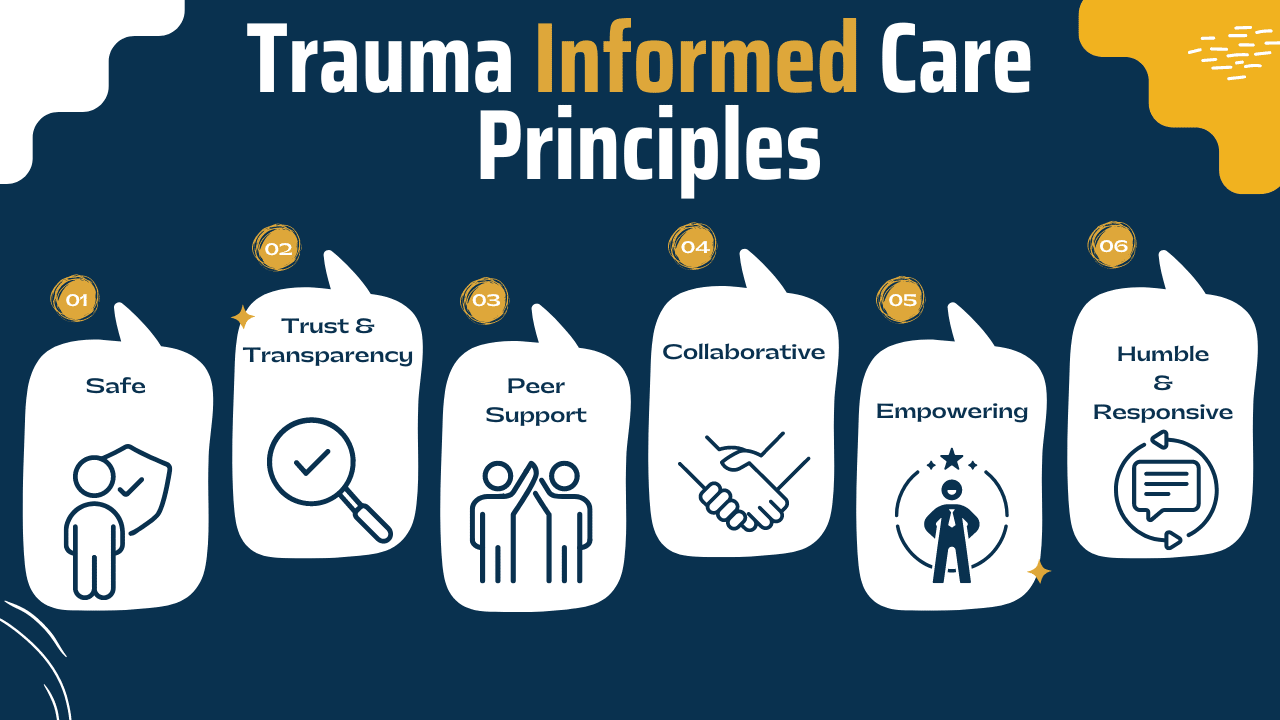

PCM offers a complete crisis management system made up of prevention, de-escalation, intervention, and reintegration that perfectly aligns with the core principles of Trauma Informed Care. This means PCM’s curriculum, instruction, guiding principles, and procedures directly aid in fostering an environment characterized by safety, trust, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and respect.

Comparing the precise and evidenced-based PCM approach to other crisis management systems in implementing trauma-informed care is like comparing a surgeon to a paramedic. While both are well-intended professionals who examine, evaluate, and treat patients, the paramedic has general medical knowledge and limited tools aimed at getting a patient safely to the emergency room in the event of a crisis. In contrast, the surgeon, who has expertise in both averting and treating a crisis, is responsible for the preoperative diagnosis of the patient, for performing the operation, and for providing the patient with postoperative surgical care and treatment. The two just aren’t comparable. And neither are the trauma-informed approaches of PCM as compared to other crisis management systems.

Trauma Informed and Rooted in ABA Since 1981

In fact, PCM has always been trauma- informed. Traditionally, many schools and facilities take a “what’s wrong with you?” approach to addressing behavioral issues. Trauma-informed care shifts this perspective from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” by having a complete picture of a person’s situation and life — past and present — as means to individualize education, treatment, and support. This approach is fundamental to Applied Behavior Analysis, or ABA, as it seeks to determine the root causes of behavior based on both the current environment and the individual’s history. For example, perhaps an individual was exposed to an aversive series of events such as, as a child being regularly beaten for not completing their chores or for receiving poor grades. These past events now influence subsequent experiences with adults related to being corrected.

Technically speaking, we may be able to categorize responses to certain related environmental stimuli (e.g., an individual being reprimanded for failing to complete a task) as avoidance, response suppression, aggression, or perhaps internal responses like increased heart rate. Whatever the case, behavior analysts seek to use data from the present and the past to determine the function of the behavior and then make environmental adjustments to accommodate them. We are proud to say that, since our humble beginnings in 1981, PCM has always been rooted in ABA with emphasis on accommodating individuals with past traumas and preventing potential new traumas.

Understanding that PCM is conceptually rooted in ABA is also important because the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts compels practitioners to not only describe the objectives of a behavior change program to clients, but to minimize potential risk in ABA practice and research and to ensure the selection of the least restrictive procedures necessary for effective treatment. All PCM’s procedures adhere closely to this code while ensuring procedures are in no way harmful, degrading, painful, or dehumanizing.